The Last Surviving Kohlruss

Words by Ned Faux & Photos by Mark Spicer

I have to start this build feature/interview/history by saying how truly flattered we are to be given the opportunity to cover this story. Not only has Mark Spicer managed to undertake the most epic resurrection of any VW you are ever likely to see, but it’s also a chance to hear first-hand about the highs and lows of what it takes to acquire a real piece of history, in a state that so many would consider only good for recycling, and turn it in to a usable vehicle that will be enjoyed by Mark and his soon to be wife Evelyn (also a Vintage VW enthusiast) for years to come.

Over the last few years we have seen more and more of these radical early bus builds going on, with a handful of major players pushing the boundaries of what can be accomplished, while still keeping some sort of integrity for the bus it was the day it rolled off the production line in Wolfsburg. I’m sure many of you will know of the notorious Kempes Bus? This was also built by Mark. The Kempes was one of the first of these types of extensive builds. The bus was found half-buried in the woods and had to be extracted with a digger. These days it seems not a day goes by without seeing a bus on social media being forked up or rescued by helicopter, but the Kempes was certainly one of the first to need heavy machinery to start its journey back onto the road. It’s one of the buses that I personally think paved the way and inspired so many to hunt out and rescue some of the oldest and rarest Type2s that previously would have been left for nature to finish what it started. There is so much to talk about when it comes to the Kempes that I could fill the whole magazine (maybe another time) … but today we are talking about the Kohlruss.

Before I start talking to Mark I’m going to do my best to explain briefly what a Kohlruss is and why it’s such a big deal to see one on the road again. First, don’t be surprised if you’ve never heard of one before. If you’re not a coachbuilt VW fan the chances are you will never have come across the name Kohlruss Carosserie. I mean … why would you? Up until recently there wasn’t a known survivor – just photos and very vague history, a vague history I’m going to try my best to run by you now.

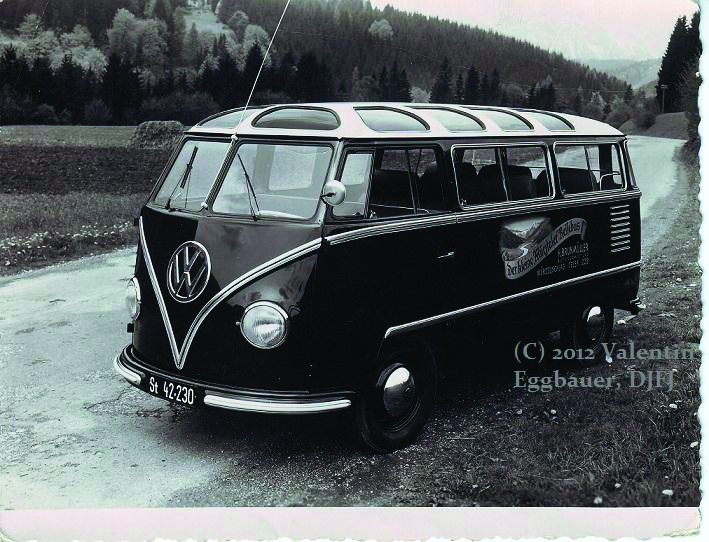

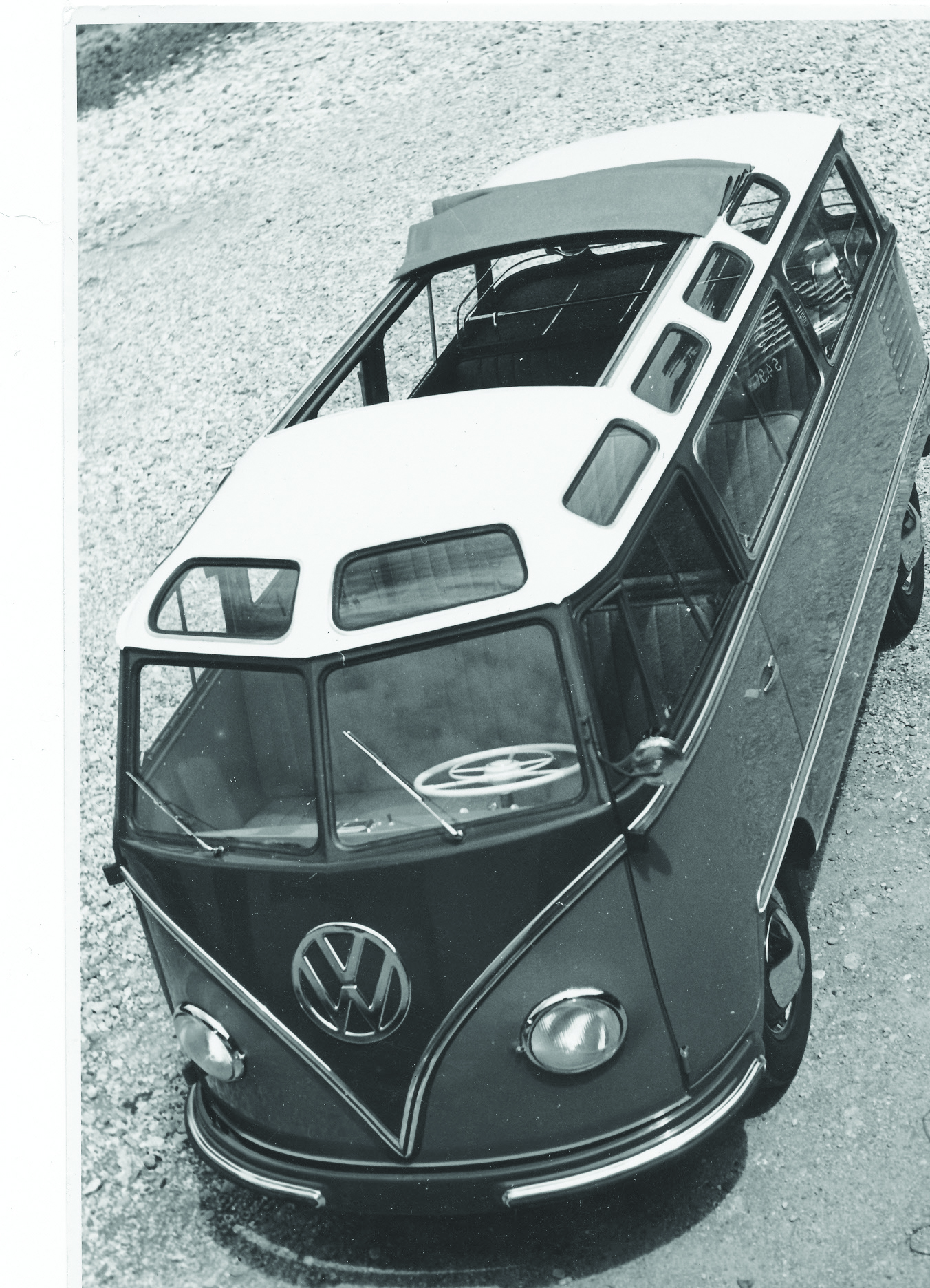

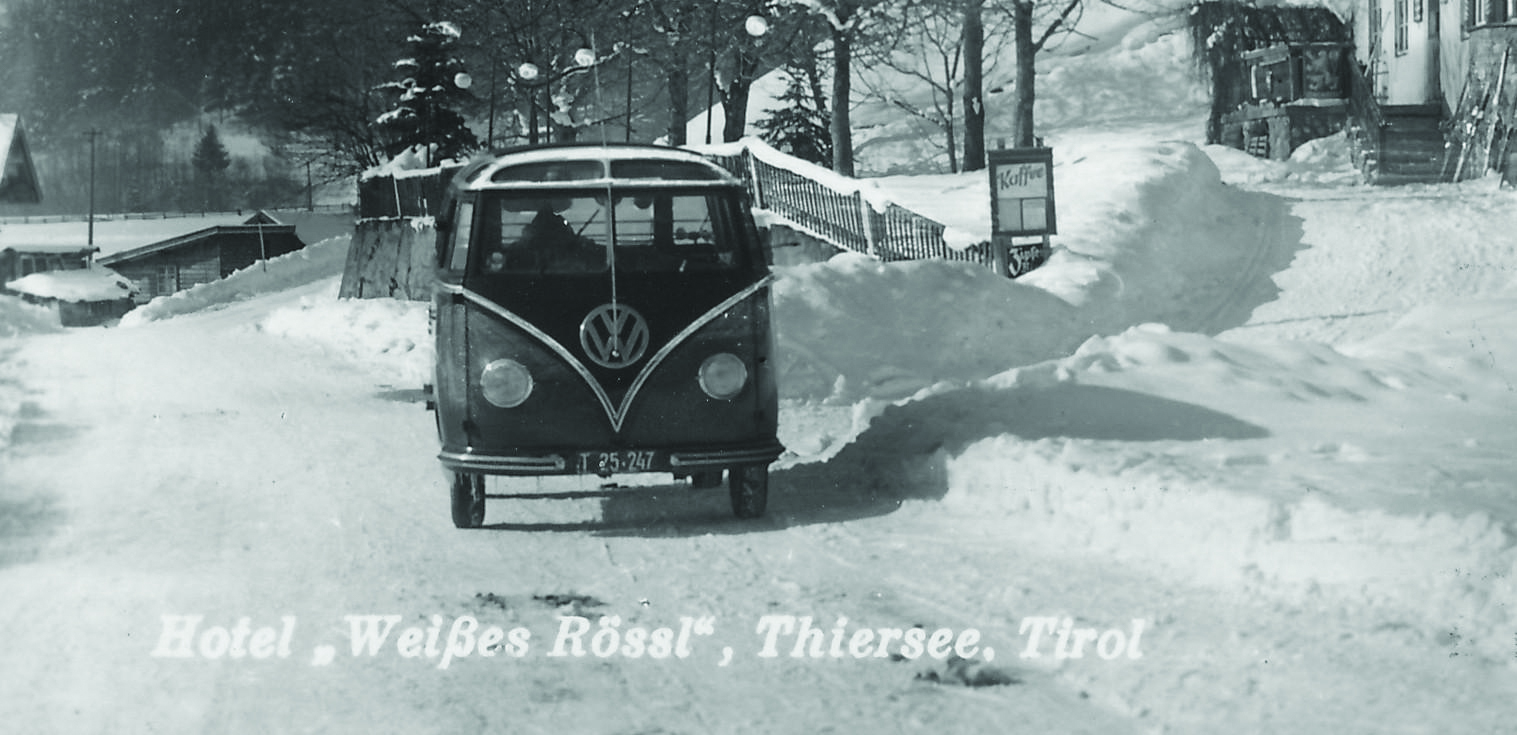

Until Mark acquired this bus I had only ever seen the library black-and-white photos I had on file, which I had collected from the internet over some time hoping to one day gather enough information to write an article about this strange conversion. I definitely never thought that I would be writing about one on the road in the UK. Although many describe the Kohlruss Type2 as a “coach built”, I would say it’s more of a Type2 adapted by coach builders rather than the more common method of re-bodying the whole vehicle. Over at Kohlruss Carosserie they took a Samba Deluxe and made it … well … even more Deluxe.

Hans Kohlruss was a coach builder who worked out of a shop in Austria’s capital, Vienna, and also in Salzburg. The Salzburg building survived until this year but was recently demolished, and I believe it’s where the famous picture of the buses lined up outside was taken. The shop in Vienna is long gone and has now been replaced by office buildings/flats. Hans is also well-known in the vintage Beetle community for his Kubel/KDF/Steyr 55/50 hybrid which was produced in the 1940s. I don’t seem to be able to find out how many were made, but looking at variations in the bodies from old photos they seem to be an extremely low volume vehicle. When the 1950s came around and the introduction of the Type2 had spread across Europe, Hans and his team turned their attention to doing a new luxury Split Screen bus as well as other bigger tourist buses of the time, one-off coach built cars and general car body repairs.

There doesn’t seem to be a great deal of information out there regarding the company. As I write this, some guys very interested in Kohruss history in Austria have managed to track down a man who worked at the coach builders and some information is apparently on its way regarding the conversion and how many were made, etc. It’s unlikely that this will get to us in time for this issue but we will make it available to anyone interested once received. So what can I tell you about a Kohlruss converted Barndoor? Everything I know is from studying photos, word of mouth, myth and, to make it all a little more awkward to make sense of, there happened to be other companies putting their own spin on the Type2, including a very similar-looking conversion by Karl Schreiner. This can make it particularly difficult when attempting to work out a history from photos.

Mark met an old gentleman in Austria whose dad had a VW Deluxe and a Kohlruss Deluxe for his taxi company. We asked him why he’d bought the Kohlruss and he said that when brand new, the Kohlruss conversion Deluxe was more expensive than the VW Deluxe, but the Kohlruss bus he bought was 3-ish years old and the VW bus was brand new. He couldn’t quite afford two new VW buses, and the Kohruss being 3 years old was then cheaper than a new VW one. They were the first two cars his dad used to start his taxi company, which still to this day exists from his house although he has retired. There was another reason too: that Kohlruss had a Porsche 356 engine in it and was much quicker than the VW Deluxe, although he did make a point of telling us that it also used to eat gearboxes; he recalled that they swapped it at least twice.

What the coach builders would do was to buy a brand- or even used new Type2 and adapt the body panels to make a fully panoramic version. From what we can see, the general market for these vehicles was hotel buses and luxury taxis, with most being sent up the Austrian Alps to be driven by tour guides. This would explain the need for the panoramic roof, so the hotel’s top-end customers could take in the view on the steep mountain roads. There are many variations of Kohlruss built Barndoors and it’s said that two buses were very rarely identical as to the way looked after leaving the workshop. I tend to agree with this opinion after studying photographs. I can’t work out if they were constantly attempting to perfect the look to finally end up with a product they could work on as a sort of small number production line, or whether Hans allowed his workers a certain amount of artistic licence with each project.

Most of the buses were delivered as panel vans. They would then have been fitted up top-spec with deluxe dash boards and dealership optional extras with no expense spared.

The roof was a Samba style with a full-length sunroof. I do have a photo of a Kohlruss bus with no ragtop but oversize Samba windows the full length of the roof. I consider this to be one of their later projects as it has a rear bumper (pre-’54 buses weren’t fitted with them). All the Type2s they worked on had a few trademark similarities, the first being the most obvious: two large skylights over the cab area, often with Samba windows enlarged. They also had two long sliding windows down the driver’s side, replacing what would have been four original square factory-fitted apertures, and one slider on the passenger side with the original cargo doors similar to a standard Samba (apart from extra trim). The shape of these larger windows resembles what you would see in the side of a Bay Window bus. I wonder if this is where the designers at Volkswagen got the idea from, as this style of side window was used throughout the Type2 range from the end of 1967 onwards.

As if the factory deluxe trim wasn’t enough, all the windows were fitted with extra handmade aluminium trim which was stamped with an individual number, so once the bus was finished it would be apparent which window it had been made to fit, all finished off with a Kohlruss badge on the other front wheel arch under the oversized extra handcrafted side trim. The van’s insides either had a coachbuilt seating arrangement with higher back seats compared to the VW items, or had original VW seats in them. The headliner in Mark’s had the same moleskin style finish and look to it and the ragtops were 5-fold items and supplied from the Webasto company with ash frame supports all round the hole edges.

All the sliding side windows, in fact all the windows in the rear, were hand formed and lined inside with a thick ash frame individually made for each window. The insides of the window surrounds were vinyl covered with piping around the edges to give a factory-style finish. The insides of the side panels and long panels and cargo doors were also reinforced with ash frames curved to fit the side profiles, to provide strength and make the vans more hardwearing.

Mark’s van also had wind deflectors for the side windows, all hand formed in brass and then chrome-plated again, stamped with a number to designate the window they were made for. Of all the Kohlruss pictures I’ve seen, I think this is the only one with that feature.

Another option seen on a few Kohlruss buses (most famously the Little Mozart bus), and fortunately found on Mark’s bus, is the centre-mounted roof aerial. What’s odd about it is that it’s designed to pivot and can be moved by the driver or passenger to point down or in a different direction. This could have been for a few reasons – low tunnels or to be swivelled to get a better reception seem the obvious ones.

I was told that all the buses Kohlruss built were LHD, but I found a photo on thesamba.com that looks very much like it is RHD or at least has left-hand side cargo doors. I can see no real reason for them to have built a RHD bus for use in Austria as they had not driven on that side of the road since the 1930s. The other possible explanation is that it was a special order bus destined for import, or even that it wasn’t a Kohlruss at all and had been converted by one of the other coach builders at the time.

How many were built I sadly have no idea. As I said before, we might have a better idea when Mark receives more information but for now it is just speculation. I personally think the number of vans they converted will surprise us. I say this only because of the number of surviving photographs, but then again of course there are loads of photos because the people taking them were probably on holiday! So there are lots of surviving photos but only one surviving bus, and that was a bus that was barely surviving when it was found.

Last year I ended up with Mark and Neils from AirMighty in a strange pub for a very late night drunken lock-in. I asked Mark, “So what are you doing for work at the moment?” He replied, “To be honest, I might just fuck it all off and go full time on the Kholruss.” He did! I will let him explain …

Q: Hello mate. It’s been a while. I hope you guys are well? So, we have a fair bit to get through. As I’ve already said, you are no stranger to large projects, e.g. The Kempes. How did you guys end up with your obsession for vintage Volkswagens?

A: Hi Ned. Ah, that’s an easy one. … I think it’s my Dad’s fault if I’m honest. My oldest memory is of my Dad taking the door handle off his 1968 Beetle and me taking it out of his tool-bag to play with (and being told to leave it alone). I was about 18 months old and he had sold it by the time I was two years old to buy a 1975 Golf LS – which later became my very first car when I turned 18, and is parked in my garage at home to this day. When I was 19 I bought my first Split Bus and again I still have that now, although that’s another story.

Q: What about the Kohlruss? From what I’ve seen it looks like one hell of an extraction. How did it end up in your hands?

A: It was the strangest thing, and absolute pure luck (or bad luck depending on how you look at it) – A set of strange coincidences which ended up with me not knowing I had even bought it. So basically I fixed the Kempes and had a few years enjoying that. I really, really didn’t fancy another big project and I was happy with just appreciating it. Then one day, five to six years later, I’m on thesamba.com (as you do) and I see a guy called Günter in Austria. I had seen the black-and-white pictures of them about in Austria and it caught my eye, but that was that and I was broke. I’d just moved house and was still not looking for a project in any way. Anyway, a few months later Dai rings me up at home to chat about stuff and while telling him I never want another project and I’m done I happen to mention that the only thing that had caught my eye was that Kohlruss in Austria. The next thing he says is basically this: “Don’t do anything. I know someone who is talking to the guy that owns it” … so I do exactly as he says and do nothing for weeks. Anyway, long, long story short, Ben who is chatting to Günter lets me have his email so I can try and sort it myself. We talk and we’re not really striking a deal. I’m not sure, but looking back I don’t think I was that keen. I couldn’t afford it as I had zero free money and it was a long way away. One day I’m driving through Bristol and someone sends me a link to an advert for the Kohlruss on thesamba and it just says Pending. (I’m sat in a massive traffic jam at that point not actually driving.) I spend the next ten minutes telling Evelyn how pleased I am that someone else has taken it on and how I’m glad I don’t have all that work to do! Four days later I get a text from Ben telling me it’s pending … to me!

Q: When you first saw what you had bought in the flesh, what did you think … better or worse than you expected?

A: That’s a good one. I remember being really happy that the long panel looked saveable when I first saw it. What I didn’t want was for something in paint to be scrap – say the long panel or a door or the lid and to have to replace a section of the outside. I had it in my head that it was going to be the same bus and in the original paint, and I was a little fearful that something was too far gone. As it happened it was all terrible but I decided it was usable, so the plan worked out, more or less. I must admit when I first set eyes on it that I did wonder if I’d done the right thing more than a few times, but I’d bought it, paid for it, and was stood in Austria with a trailer, so that’s that, no going back.

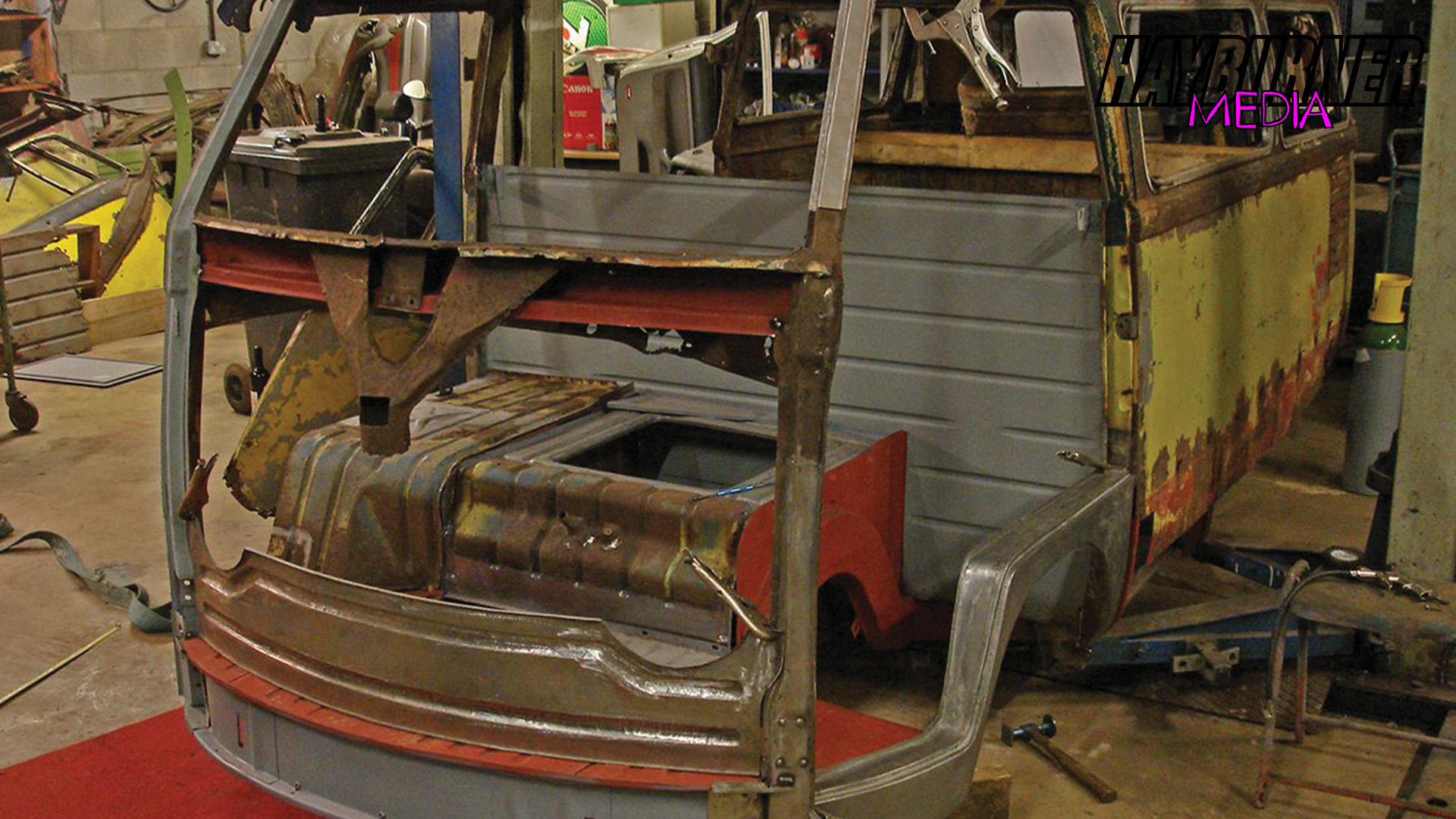

Q: I can’t imagine getting my head around the pile of rust you had acquired. Where did you decide the best place was to start?

A: The moment I arrived back at the unit from Austria, with no exaggeration I lifted the body with the forklift and the only thing still attached to the chassis was about 1 inch of the driver’s side rear support. One hit with a bolster chisel and the body was separate from the chassis. I decided chassis first and then to plonk the largest sections back together and try and assemble it. As it turned out I practically had to take the whole bus apart to fix it. The plan basically evolved as I went along. I took each panel at a time, fixing each one as I went, with the plan being to assemble it all as one big kit with all the original panels but without the rust holes in it.

Q: I know for a lot of this project you actually scratch-fabricated it yourself. I also remember you were missing a few bits and pieces. Run us through a few parts that had to be found or made.

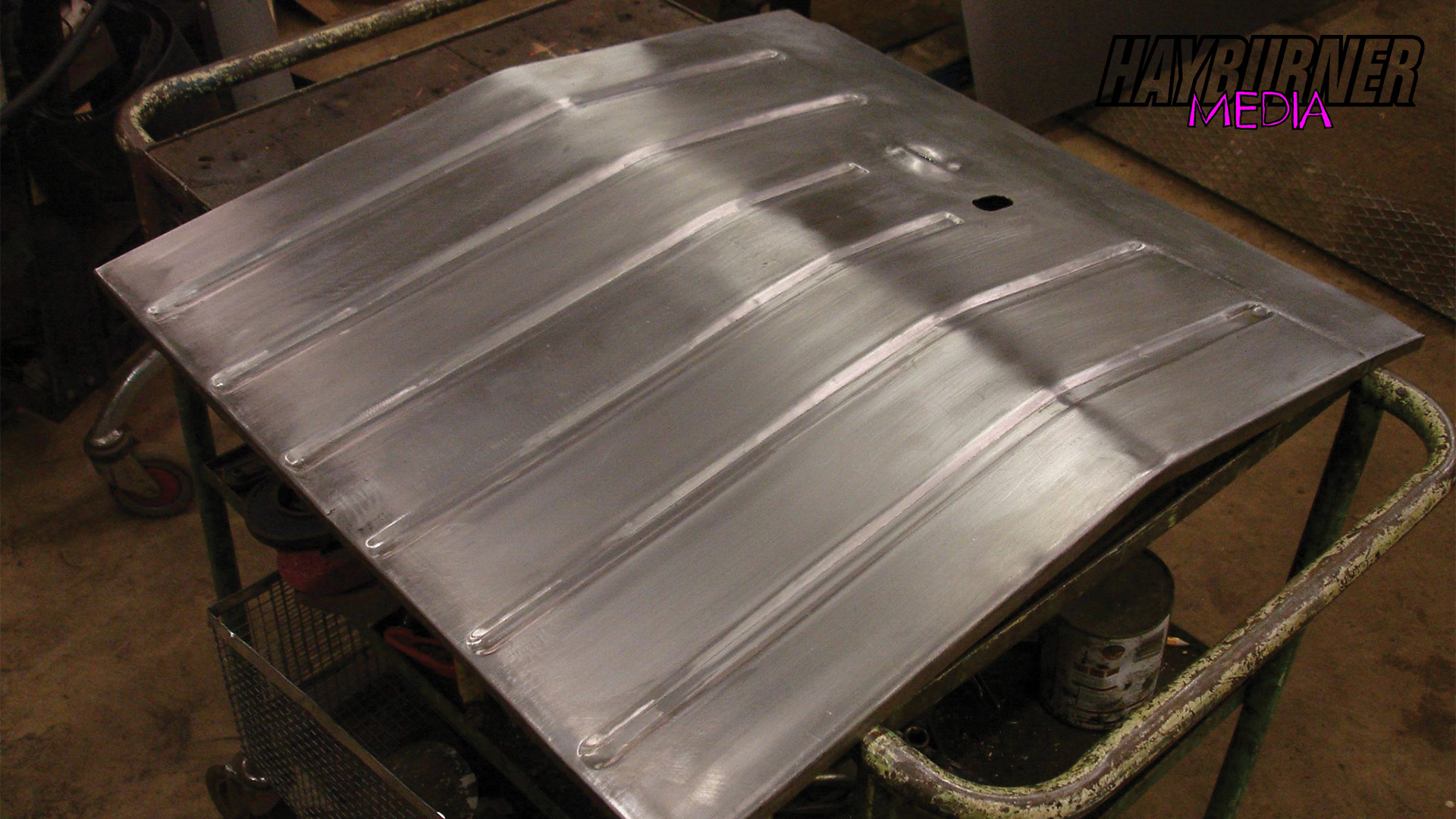

A: I wasn’t working for the second year of the project. Before I gave up my job I had purchased a lot of parts for things like brakes, etc., but there was no budget for panels so it forced my hand to make as much as I could. I made a lot of the panels but I did buy a few. I made the cab floor, both the front cab steps, headlight kick panel, tool chest bottom and engine bay trays, to name a few, and all the repair panels for the original panels. It’s so time consuming. I guess, looking back, I can see why it took me so many hours to do the van.

The other big part of this project was all the woodwork. There is a ton of ash in the van. All the side windows are ash framed; all the door panels and long side panels had ash frames inside; the ragtop is all ash framed. … I’m surprised the van actually moved with all the wood in it. My woodwork is unrefined at best and something I don’t enjoy. Fortunately Pete walked into the unit one day with lengths and lengths of seasoned ash and said, “Is this any use to you?” Someone he knew was getting rid of it and by absolute chance it ended up with me. I repaired as much of the wooden frames as I could but had to remake a fair bit too. That was testing, given I didn’t have any woodworking tools, but I got it done and was happy with the result.

All the side windows needed rubbers and new glass, so I made them all from cardboard and I matched the rubbers from the stuff that was on the ground. I got the glass cut by a local glass company and apart from the rear one which I broke when fitting they all went in and worked first time.

Basically, I think I fixed nearly everything in one way or another so I’m surprised it runs at all.

Q: Am I right in thinking you had a timescale in mind for the entire build? At what point did you decide to jack in your job to get it done? How did you manage to make that work?

A: What happened was that we were at Classic Le Mans in 2014 and I had not long collected the bus from Austria. I happened to promise Remi, who organises the Original Flat4 Drivers Club, that I would, whatever happened, be there in 2016 in the Kohlruss. I knew it probably wasn’t possible but it was in my mind the whole time. Once I got started it became clear very quickly that I was going to run out of time. I quit my job about halfway through the project for many reasons. I had been commuting 100 miles a day for 12 years and I had become very bored with IT and needed a different direction … whatever that might be. So after I did that it meant I had time again to try and get the van done. Although the little money I had saved soon ran out, we managed to muddle through for the whole year until Le Mans and the Austria trip. The van was done on a budget of pretty much zero from that point. I had worked and given eight months’ notice before I quit, which had enabled me to buy some of the parts I needed from Tonny in Denmark who was selling up, and also all the original interior door panels from Thomas in Sweden. I’m not sure I would use the words “make that work”. I didn’t really make it work. It was hard at times to be honest, and if it wasn’t for Evelyn keeping everything going then I wouldn’t have been able to think about finishing the van.

Some of the van is still borrowed: the fuel tank and tyres are not mine. I couldn’t afford them but I have some great friends who helped me out and let me borrow them. And I still need to find a tank to this day.

Q: This is a hard question to answer because there were so many aspects, but what was the most challenging part of the project?

A: Can I pick two? If so, I’m going to say the whole back end and the roof. One of the biggest issues I had with the whole project wasn’t the rust but the collision damage. The back – and front, in fact – had been pranged on both sides (but never in the rear lid, fortunately), and had been beaten back out by old-school methods. I think with no exaggeration that I actually spent three weeks on separate occasions getting the rear engine lid, rear horizontal firewall and everything aligned. Just when I thought I had it, I would sneeze on it and the whole lot was out. I nearly gave up a few times and it drove me nuts. The roof was also tricky. I had to take it off in four sections and then repair all the missing parts up to where it would join the roof gutter. Except I didn’t have a roof gutter when I did it, so I did it all by measurement and had to factor in some of the coachbuiltness of the roof openings. Also, one side was heavily tree damaged so it was stretched. Eventually I had the whole roof sitting on the floor of the unit and the roof gutter complete on the van. I was very relieved when it was all aligned and the three cuts and the one that had completely split through were all lined up and I could stitch it together.

Q: We can see that you managed to save as much of the original panels and paint as possible. Most Barn Door panels are available off the shelf these days. Were you ever tempted to scrap the parts that could be saved and just replace them because of convenience and the timescale?

A: Not really, although I think I could have shaved a year off the project by doing so. I’m not knocking people who do that; it’s just not for me. I think too that this bus was rare and enough had survived. It would have been a real shame if it had turned into a new bus. From day one I wanted to drive this bus and not a recreation of the bus.

Q: Were you ever tempted to fully restore the Bus?

A: I still think to this day that it would be amazing in fresh paint and fully restored, but if I did that it wouldn’t be the same bus. It’s a little too wobbly and rusty to actually paint it. I love how it looks now too much to actually do that. I’d have lost all its character and history with new panels. And painting it would have been a project I couldn’t have found the energy for, I think. The irony is that if it had been found in mint condition in a garage somewhere in Austria then I would never have been able to afford it. The fact that it was so rough meant a normal guy like me could buy it, and now I get to enjoy it so I’m glad it was as bad as it was.

Q: Did you do all the work yourself or were there jobs that you needed help with?

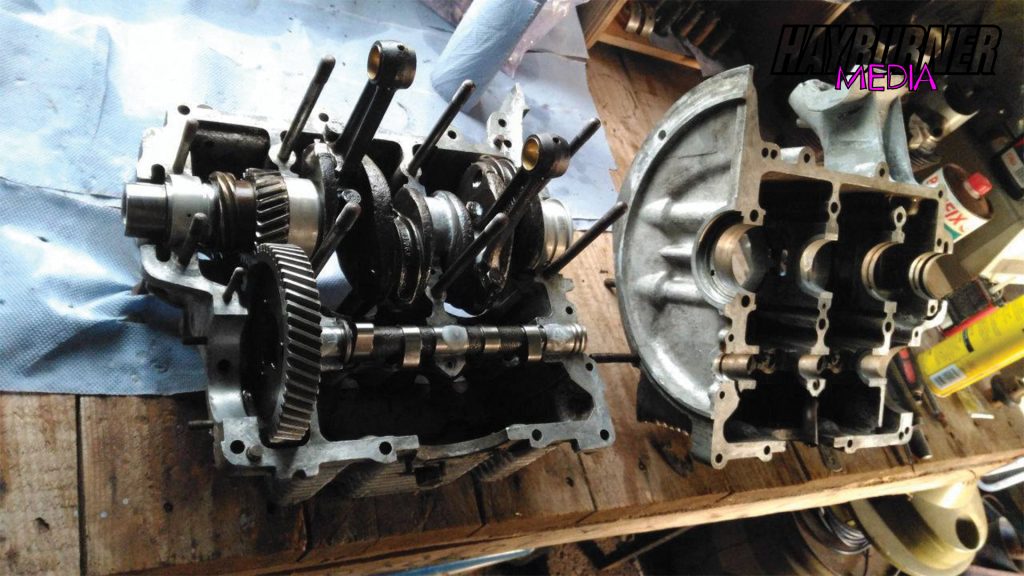

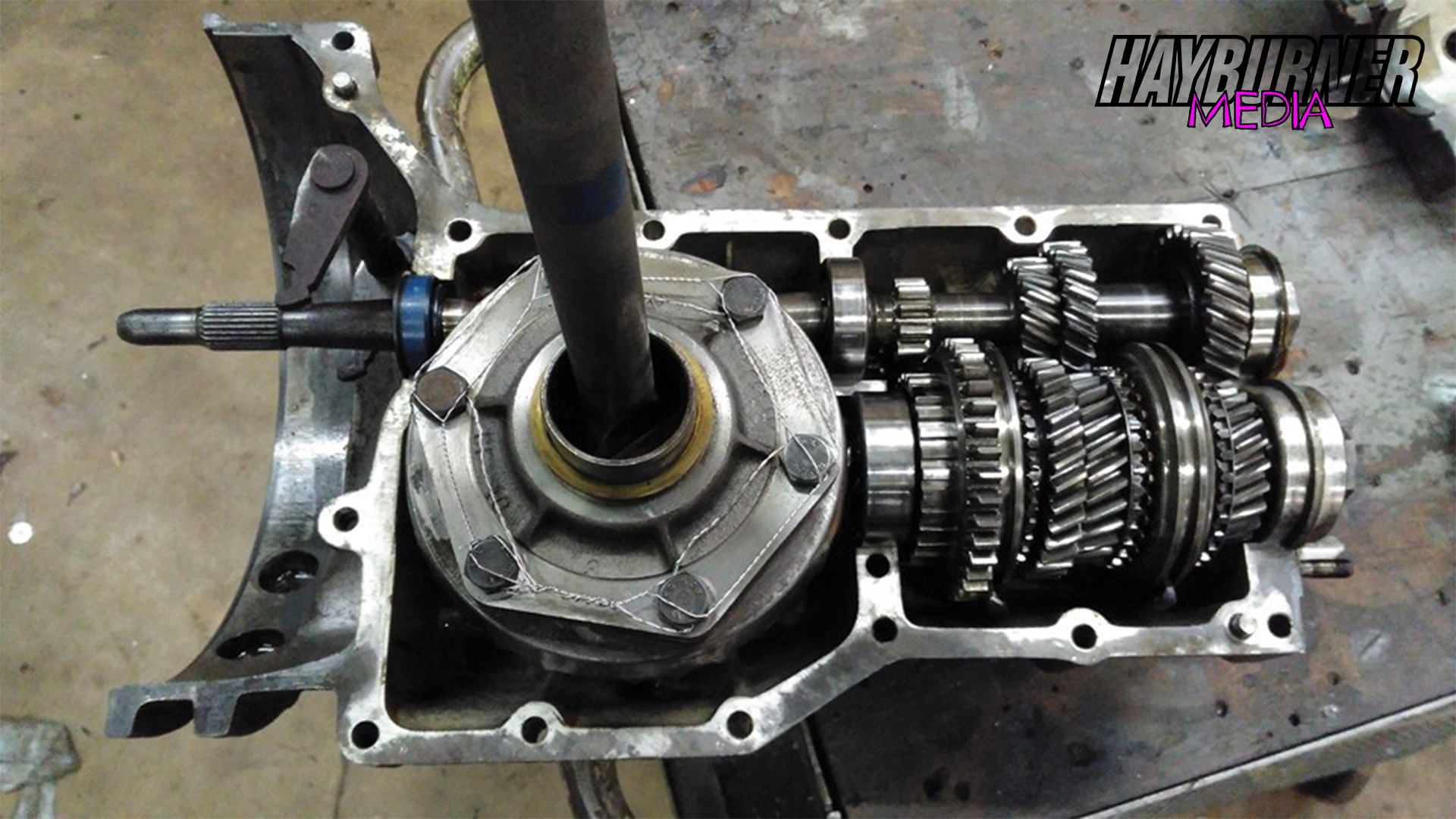

A: I have a good friend at the unit – Pete – who makes a great cup of tea. He made two years’ worth of tea and often lunch, and for that I’m very thankful. As far as the bus is concerned I think I did it nearly all myself apart from a couple of weeks before Le Mans, when a couple of friends came over and helped me get the engine bolted together and the gearbox in. Those three days of help definitely helped me get the van done in time!

Evelyn also helped me strip the red paint off when we first got the van, to get back to the yellow paint. That was one of the first things we did. I tend to work on my own; I’m a bit of a plodder and things have to be right to a point. I think if anyone had helped me they would have tried to kill me in the end 🙂

Q: You made the deadline. Tell us a bit about your journey to Classic Le Mans. Ben tells me it had a few ups and downs.

A: Ha ha. A few ups and downs. … So on the night before we left for Le Mans, the bus had never turned a wheel, never driven anywhere. It had no ragtop, just a huge hole in the roof. So by 2.30a.m., Pete (cups of tea Pete) helped me find a huge bit of galvanised steel in the field outside and we built a wood frame and dropped it in. The number plates had just turned up but I didn’t have a chance to fit them as the hole in the roof seemed more important. I went home knackered, with several million jobs still to do and everything untested. All I said was that I was going to drive it from the unit to home – about 11 miles – the next morning, and if it drove ok then we would pack it up and drive it to Le Mans Classic. The next morning I drove it home on my own. It drove.

There were still a ton of issues but I decided that after all that work, nearly 3000 hours, issues getting it registered and it going down to the absolute, absolute wire, that I had come way too far not to drive it … I was going to drive it! So Evelyn and I pulled the camping box from the Kempes into the Kohlruss that morning and packed it all up, and – the most nervous I have ever been – we set off.

Within eight miles of my house we were on the M5 and I knew things weren’t going great. The “fresh” 25hp engine, rebuilt with old parts, wouldn’t go over 35mph flat out. We already knew we were going to miss the ferry, even before meeting my mate in his ’59 Beetle near Cirencester and then getting to Portsmouth. We made it to meet him but it became evident that the brakes were the issue. I backed them off but every time I used them they would tighten up. Anyway, to take a little strain off the van and hopefully give us a chance of making the ferry, Evelyn and as much of our stuff as possible went into the Beetle and we set off again.

I remember being on the M4 and on my own, driving the van I had spent all this time and effort on, and I got a little emotional for a minute or two that it was actually moving and driving. Anyway that didn’t last long. The brakes were still binding badly and to top it off, when I pulled onto the M27, as I shifted into 4th the clutch pedal snapped off. I almost gave up then through tiredness. We had almost certainly missed the ferry. So I set off down the M27 in 3rd. I couldn’t get the gearbox (which I had started to realise was not good) to shift into 4th. After about four miles I managed it and somehow got to the ferry port with only 4th gear. The ferry was late leaving and we were the very last in the queue. … And that, as it turned out, was the easy bit!

We fixed the clutch pedal by taking the floor panel out and cable-tying on a 17 mm spanner at one end and putting a brake wind back tool through the other end to act as the pedal. It worked great and meant we could actually drive onto the ferry!

I never give up, but that night I got to a point where I felt like I was spoiling it for everyone else. I actually said I was going to quit. That was at 3a.m., totally knackered. We were in the middle of nowhere on a back road, lost in France. The Kohlruss was stuck fast in 1st gear, its 6 volt battery dead and the brakes almost seized on. We had stopped all afternoon and all night with repairs to the van. The generator was only putting out enough volts to run the coil but not the lights. It would run itself but not charge the battery or run the lights, so I had driven miles and miles in the middle of the group with my lights off. Despite having the world’s simplest brakes, I had backed everything off to the max and yet it was still binding badly and the untested ‘it will be fine’ gearbox was now so bad that putting it into 1st was borderline terminal. Second rarely went in and 3rd and 4th were tricky to get too.

So there we were, at 3a.m. in the dark, in the middle of nowhere, stuck in first gear, no power at all, and I was the only one on 6v with the brakes stuck on, so we couldn’t even push start it.

The 6v battery was connected to a 12v one to get some power into it. I bent the gear selection rod, forcing it out of gear, but I managed to get it out of 1st and then never used it again for the rest of the trip. The brakes were still a mystery at that point and nothing could be backed off any further, but we finally made classic Le Mans at 5a.m. What a trip!

We charged the battery at Le Mans and travelled back in the light, which meant the generator’s low voltage wasn’t an issue. The brakes came apart at Le Mans; it was the return springs that were causing the problem. There wasn’t enough spring to pull the cylinders back after each use, so I re-bent or created a longer route for them to take and that fixed it. The gearbox never got put into 1st again … and that clutch pedal, it lasted the whole trip with no extra work. 🙂

I’ll mention my thanks at the end of this piece, but all those people on that Le Mans trip were stars. They wanted that bus there as much as me, and without them it wouldn’t have made it!

Q: How is the Bus to drive now you have had put a few road miles on it?

A: Fantastic. After the work I’d done in Le Mans we made it back with no further repairs. Then the week before we set off for Austria I went through the bus, spent 12 hours a day for a week on it, and fixed up another gearbox (it had a failed diff) to replace the dodgy one that had given me so much grief. I sorted all the niggles and issues the bus had. Evelyn and I drove, I think, a 2500/3000-mile round trip and travelled the length and breadth of Austria with not one issue. I still regularly use it and it’s absolutely perfect (except that it leaks like a sieve on rainy days).

Q: With hindsight, is there anything you would have done differently with the build?

A: Hmm. No, not really. I think it pretty much went to plan given that I didn’t really have a plan. I think having a longer deadline would have been a lot less stressful, and maybe a budget of zero for the best part of the build was also a bit of a bind at times, but I’m really happy about how it turned out overall.

Q: What are your future plans for the Bus?

A: The engine that’s in it now, the 25hp, was originally built for the Kempes, and the 30hp in the Kempes is due to go into the Kohlruss. The 25hp is actually quicker/pulls better than the worn-out 30hp, so that’s why I didn’t swap them before the trip.

The biggest job now is to get the ragtop finished. I have located some of the parts but I will have to make some of it. The Webasto sunroof is an ash-framed one from the 1950s and I think only one other Barn Door I know has one fitted. A little of the original survived so I can put it back as it should be, but getting it in and getting it all to work is a job for this winter.

Other jobs are to get the green vinyl covers back round the inside of the windows and also to put all the seats back in. I have now found original covers for all the parts except one. Window latches, even etching the side glass with the original manufacturer’s logo and putting the Kohlruss-style jail bars in the back window are also on my list. I’m just going to keep on at it until it’s completely done.

I still haven’t decided what to do with the paint. I’m not a paint blender person, but with the fresh metal that went in the cab door bottoms it looks a little like it has two cab steps. I may paint just the door bottoms on both sides so it looks better. I still have the last of the red paint to strip off one side, which was an overpaint of its Kohlruss colours. I will get to that soon enough. I don’t actually think this project will ever end. 🙂

Q: Do you have any advice to someone thinking of taking on a build this big?

A: Dont! … No, I think it’s great that people invest so much time and money in these old vans and I love following other people’s builds, but with something as bad as the Kohlruss you really have to be prepared for the hours and the lack of progress. A 12-hour day can have nothing of substance to show for it and that, day after day, can be pretty demoralising. I think I underestimated the hours it would take – not the money because I made a fair few of the things I needed so the budget was low – but the time was a real pain at times.

Q: With any project of this magnitude I imagine a few acknowledgements are in order. Who would you like to thank?

A: The first one has to be Evelyn. I can’t think of many (or any) people who would have put up with all the hassle, the long evenings on her own, the not having any money while I worked on the van day after day, the whole absolute stupid plan that was the Kohlruss. She is an absolute one-off and we’re getting married next year, I’m super happy to say. She is amazing and I’m a lucky guy to have her!

Pete, for all the tea, food and chats we had. He is a guy who has very little and yet would share his last bean with you. I’m very grateful to him! Clive, whose unit I rent. He put up with my Kohlruss strewn about the place for two years and always believes that these old wrecks will actually drive out of there one day. He’s guy who is never lost for words, except for the day I asked him if I could use the unit and showed him the picture of the Kohlruss. 🙂

Seb needs a mention for all the endless measurements he gave me. He works as a sound engineer and does odd times and hours, and he was often near a more complete Barn Door during the day than I had sat in front of me, so he texted me a load of measurements when I needed them. He also lent me bits from his van so we could actually get it moving – a big thanks for that. Biff and Kieran, who gave me three days’ help a couple of weeks before Le Mans, helping me with the engine, gearbox lifting and all those shitty things. Those three days made the difference!

The Classic Le Mans crew, Evelyn, Biff, Dai, Richie, Ben and last but not least Mo. … I think it’s all a trip we will never forget. 🙂 Thanks for all your help and encouragement, especially at 3a.m. when I had had enough. In Austria there are Günter, Valentin and all the Bustards who made us welcome and have done so much research on the Kohlruss coachbuilders. There is much more information that is going to come out and maybe Hayburner can run a follow-up story when we have more history to print.

I would also like to say a massive thankyou to all the kind comments and the encouragement of everyone who followed the restoration on the Facebook page. Without doubt that gave me the push I needed to keep at it day after day to get it done, not to mention all the pictures and history that came from them too.

There were a lot of people who kindly sent me parts or gave me bits of panels to cut up that I could use to save the van. I won’t try and name them all for fear of missing people off, but a massive thankyou to everyone that did that too!

If I have missed anyone, I’m really sorry, but a massive thankyou again to anyone who helped in some way with the Kohlruss project.