Aircooled Escobar – Porsche RSR’s and the King of Cocaine

Words by Mike Freeman

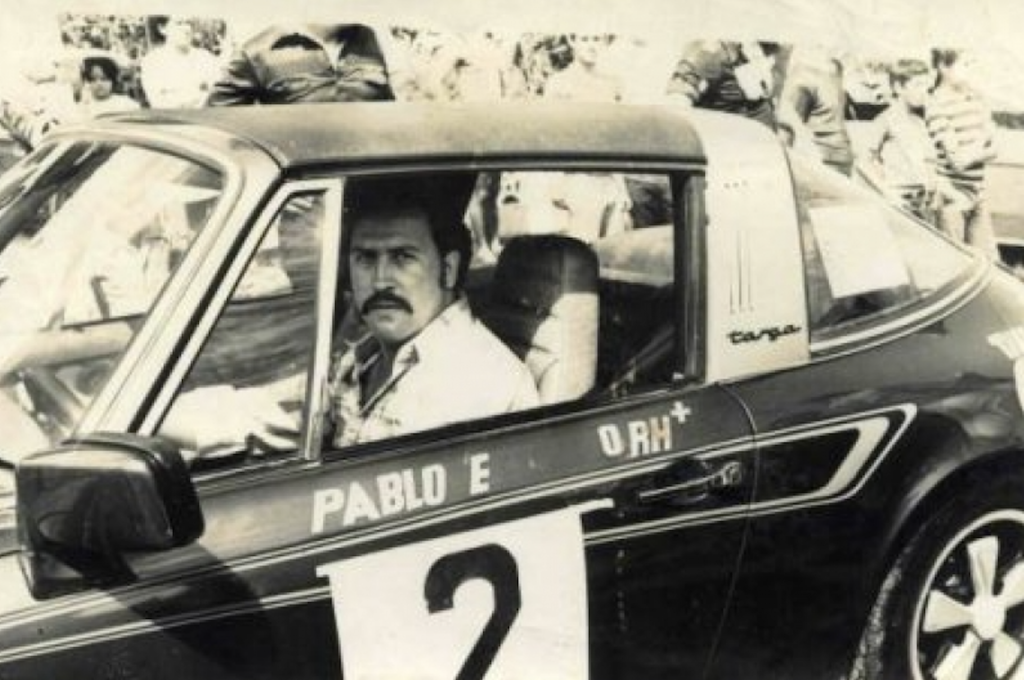

Columbian drug lord, narcoterrorist well known for being the wealthiest criminal in history and all-round pretty damn scary guy Pablo Escobar was no stranger to the press. That’s why it surprised us to learn that Escobar’s first mention in the late-70s newspapers wasn’t anything to do with being the “King of Cocaine” but for racing Renaults and air-cooled Porsches.

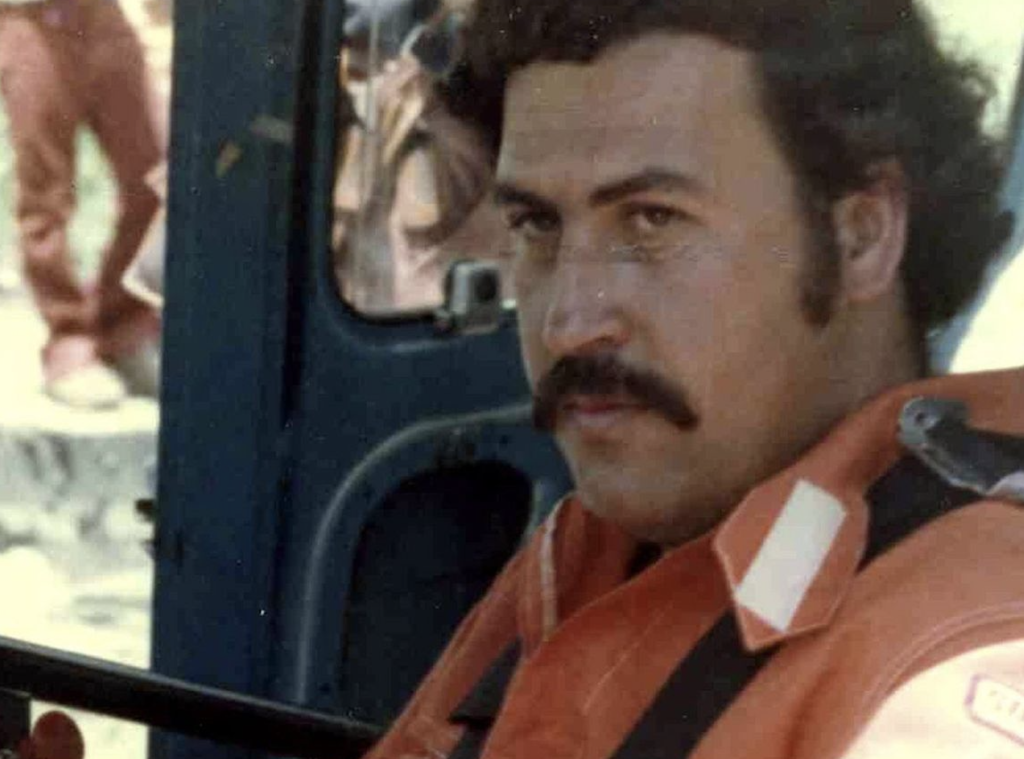

To give you an idea of the man we are talking about, Escobar at the beginning of his “career” was engaged in selling counterfeit cigarettes and lottery tickets and participating in motor vehicle theft. Through the 1970s he was involved in kidnapping, murder and setting up the biggest cocaine route known to this day, shipping over 80 tons of the white powder from Colombia to the USA a month. His drug network was commonly known as the Medellín Cartel, constantly warring with rival cartels both domestically and overseas. All this resulted in brutal massacres, the murder of police officers, judges, locals and prominent politicians, ending up with Colombia becoming the murder capital of the world. Commonly known as “The King of Cocaine” by the end of his career, Escobar was the wealthiest male criminal in history with an estimated “known” net worth of $30 billion by the early 1990s (equivalent to about $55 billion today).

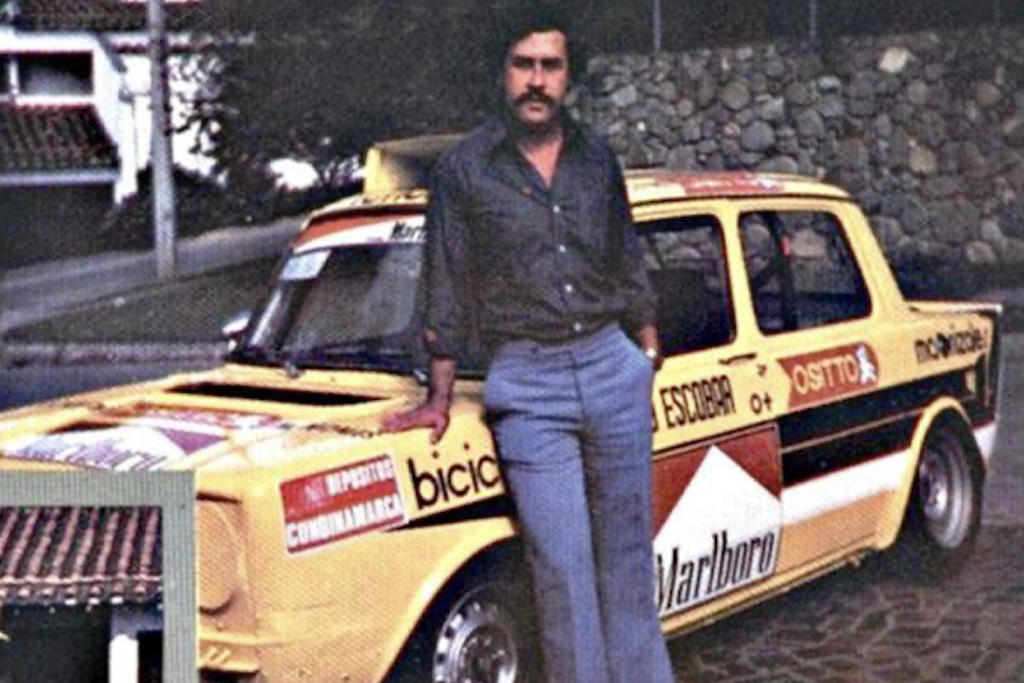

Long before Escobar’s obsession with narcotic smuggling, his drug of choice was speed… not the kind he could sell for profit but the kind he found behind the wheel of a Porsche 911 RSR or at that time various Renaults. At that time in Columbia, the Renault 4 was the equivalent of Germany’s Beetle, Italy’s 500 or Britain’s Mini. It was known as the car that got Columbia moving and is a very popular cult car in the country to this day. Escobar had a passion for these little French cars up to the point of his first arrest in 1974 while using in his Green Renault 4, and was well known in his Kingpin days to send these cars as gifts to business associates.

Racing these cars over the mid-70s had brought Escobar to a competitive level and he entered the inaugural Copa Renault 4 Championship at the Autodromo Ricardo Mejia circuit in Bogota alongside his cousin Gustavo Gaviria, who was known to be a far better driver.

Escobar turned up at the race with four cars – one for himself and his cousin and two spare. Also competing in the race were the notorious “Ochoa brothers”, leaders of the Medellín Cartel – the same cartel to later bring the Colombian nation to its knees with the use of corruption and unimaginable violence.

At the time of this race, although Escobar was rising through Colombia’s criminal underworld, he was still known by the press and locals as a popular, successful used bicycle trader alongside his brother Roberto who had started to invest in property and used his wealth to help the less fortunate. If you study some of their old racing photos you can see their bike company name “Ositto” as a sponsor plastered down the side of the race cars. Sources in the Colombian racing world at the time recall how they had their suspicions about Escobar’s income, as he would arrive at the track by helicopter, and champagne and women flowed after a race whether if it was a success or not.

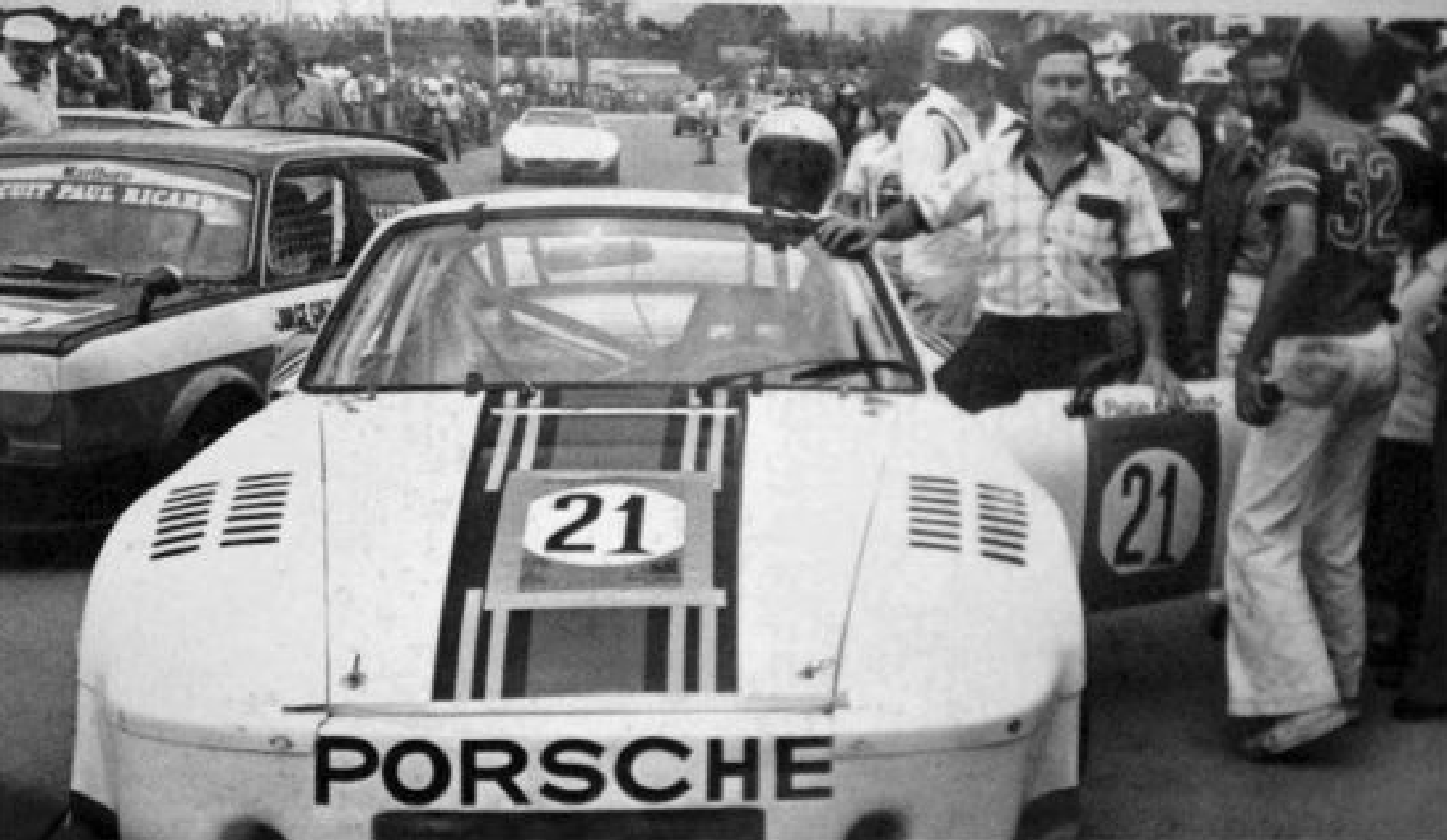

The power that these little cars put out was not enough to satisfy Escobar. In 1973, he found himself in a Porsche 911 RSR (one of rarest 911 RSRs in existence with only 15 cars built for the IROC series). This was a known car that had been originally raced by Emmerson Fittipaldi in the ’73 IROC Championship.

As far as records go he was an enthusiastic but mediocre driver. The cars he drove were always thought to be a higher spec than the other drivers had which made him slow in the corners due to his ability but uncatchable on the straight due to the extra power. Officially none of his cars were ever disqualified. But, saying that, would you want to be the man responsible for disqualifying Pablo Escobar? Not surprisingly, Escobar was not above using some of his “professional” methods as a competitor. Once he used his connections with the local police to make sure his main rival in the series was held up from getting to the track, for what would be his first nationally televised race. “The police kept us on the side of the road for hours checking papers”, said Alvaro Mejia. “We got there only minutes before the start.”

In 1979, and six races later, Escobar was second in the championship and told a journalist – “I can’t deny it, life smiles at me. I’m a lucky man.”

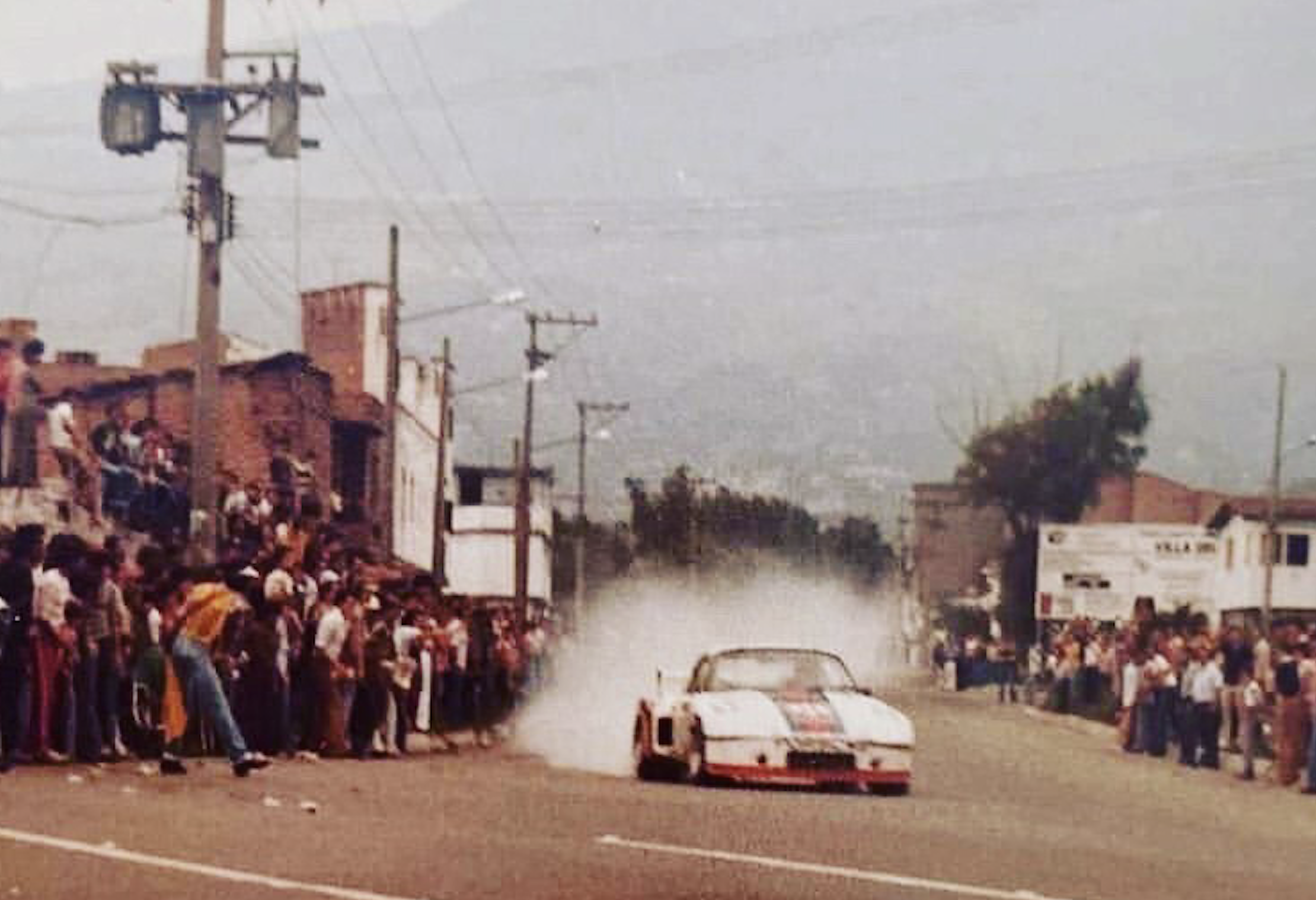

Pablo would continue to race the same 911 for the next few years all around South America and at one point converted the RSR to look like a slant nose Porsche 935. At a Medellin Hillclimb, Escobar bet his main rival and close friend Ricardo “Cuchilla” Londoño (already one of Colombia’s most famous drivers) that he could finish within 15 seconds of him. He would go on to finish eight seconds behind him in his Martini liveried Faux 935 “fair and square”. This, was known to be his proudest moment.

Soon afterwards – Escobar, along with the Medellin Cartel, funded Londoño’s rise through the racing circuit. This proved to be an excellent way for the cartel to launder money and eventually even an attempt to get Cuchilla onto the world Formula 1 grid.

Escobar’s funding secured Cuchilla a place in the 1981 Brazilian GP. His times were amazing in practice. He was clocking times in the top 5 while driving a terribly uncompetitive car. This was irrelevant as it was discovered where his backing came from.

By this time, Escobar had built himself one hell of a reputation for the wrong reasons so his licence to race was immediately denied in an attempt to protect the sport’s prestige.

Escobar met his end in 1993 at the hands of the Columbian National Police, one day after his 44th birthday. Ricardo “Cuchilla” Londoño, Escobars greatest rival, was ultimately gunned down in 2009.