The Importance of Josef Ganz – One Man’s Influence on Volkswagen History

Researching Volkswagen history has taken up a huge amount of my time over the past decade. At first it was just a necessary evil I had to suffer whilst attempting to edit a new magazine but, over time the history of this subject has become something I am passionate about and maybe even my favourite part of the job.

I first realised this research was almost becoming an obsession around 4 years ago whilst having a conversation about Tempo Matadors with Scott Carter (Cool Flo). Halfway thorough my explanation, he stopped me with “Here we go, Ned’s getting a bit ‘heavy’ again” (by heavy I think he meant boring…) After this, I thought to myself “have I been boring my friends to death?” and I decided to put a cap on my droning and save it for writing simple explanation articles on how the cars so many of us love came to be.

The great thing about a free magazine is that if history is not your thing, you can escape boredom and flick to another article that better suits you – We do try our best to cater for everyone.

The reason I talk of research is because Josef Ganz is an important name to the Beetles history that at one time had almost vanished from history and without the 5 solid years of digging by journalist Paul Schilperoord we would still know little about the man who some say “invented the Volkswagen.” If you find the following words at all interesting, I strongly recommend you hunt out a copy of ‘The Extraordinary Life of Josef Ganz: The Jewish Engineer Behind Hitler’s Volkswagen‘ (now published in English).

Josef Ganz was born on the 1st of July 1898 into a Jewish family living in Budapest.Being fascinated with mechanical technology, he started engineering studies at a young age which unfortunately got cut short when the family moved to Vienna, Austria in 1915. The following year, wishing to do his part, Josef became a German national and voluntarily enlisted in the Navy to fight in the First World War. In 1918, the war had ended and he went back to his mechanical engineering studies. During his service, seeing the world develop around him, he had dreamt of designing and creating a small car which he could sell to the people of Germany for the price of a motorbike.

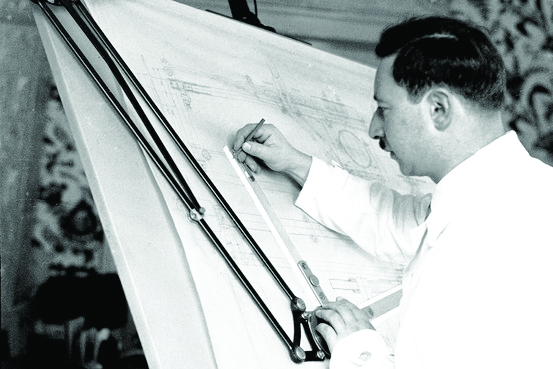

By 1923, whilst still a student, Josef had already made sketches of this revolutionary small lightweight car, it had an air-cooled rear-mounted engine, based on a backbone-type spine, independent suspension, swing-axles and an aerodynamic body. At this time, he didn’t have the funds to build a running prototype but began having articles on his car designs published in various automotive magazines. By 1927, his work was of such interest that he had got himself assigned as editor of Klein-Motor-Sport magazine. Being as his heart lay with engineering rather than journalism, he used the magazine as a tool to point out the faults with current heavy, old fashioned and in some cases unsafe cars that were only designed to ferry around German aristocrats.

Klein-Motor-Sport had become the perfect platform to promote his innovative design ideas and concepts of a car aimed at the general population. He was a close friend of Paul Jaray (an aeronautical pioneer) and supported Jaray’s streamlined body designs, whose shapes always very much resembled what is now known as the Beetle. These articles were far too much for the other well-established auto companies of the day. The lawsuits, slander campaigns and a major advertising boycott were soon to follow against Motor-Kritik Magazine, mostly lead by the man who would become Volkswagens post-war director Heinrich Nordhoff.

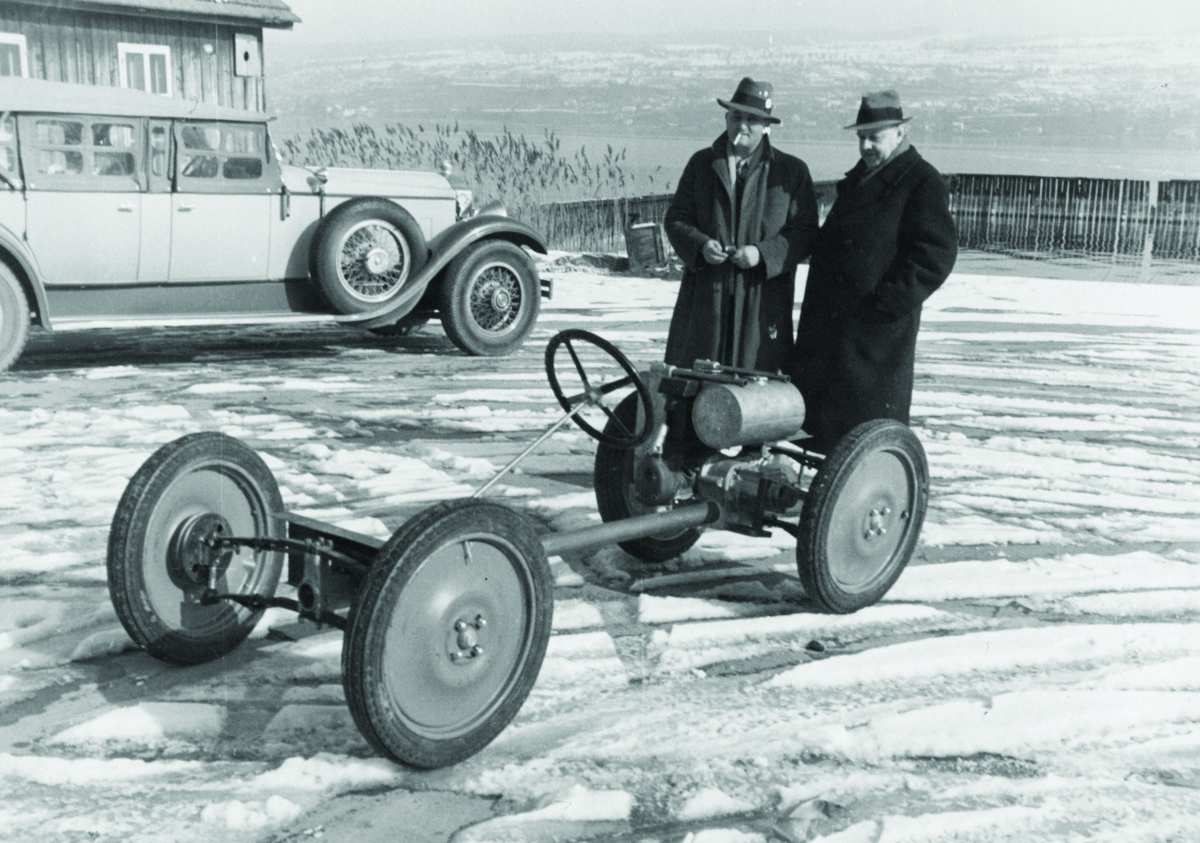

By 1929, Josef was no longer a magazine editor and turned his efforts to networking with German motorcycle manufacturers such as Zündapp, DKW and Ardie attempting to seal some sort of a collaboration to build a prototype of the small, affordable and safe ‘people’s car’. It was the company Ardie who first took a chance and accepted his design ideas.

The following year the Ardie-Ganz prototype finally became a reality and the year after, they built a second template built at Adler. The car had been nicknamed the Maikäfer (‘May-Beetle’). This was the car that really started the controversy. Once news about the all-new Ardie-Ganz and Maikäfer prototypes reached Zündapp, who had previously turned Joseph away, the company contacted Ferdinand Porsche to offer him a deal to develop the “Auto für Jedermann” (‘car for everyman’).

Many say that the ‘Peoples Car’ was Hitler’s brain child but in the years before WW2, the term ‘Car for Everyman‘ or ‘Peoples Car‘ was already so common it had become cliché. The ‘Peoples Car‘ in Germany during the 1930s was like the ‘personal computer‘ in the USA during the ‘80s and with Ferdinand Porsche on the case, already working for companies such as Zundapp and NSU, the affordable car race was well and truly underway.

Josef held a number of patents for suspension, steering and other systems. This made him extremely valuable to companies such as Daimler-Benz and BMW where, at times, he was hired as a consultant engineer and was heavily involved in the development of the first production models using independent suspension including the Mercedes-Benz 170 and the BMW AM1. At the time, it wasn’t unusual for consultants, engineers or designers to constantly flit between automotive companies. This is around the time Joseph Ganz and Ferdinand Porsche finally crossed paths. Porsche was also on the team at Benz at times, actually working under the supervision of Ganz. The two constantly disagreed on the use of 4 or 5 cylinder engines (Ferdinand preferring the Flat-4) but together they still managed to produce three concept cars. Sadly all three of these combined prototypes were destroyed during the war, the last survived until an air raid over Stuttgart in 1945.

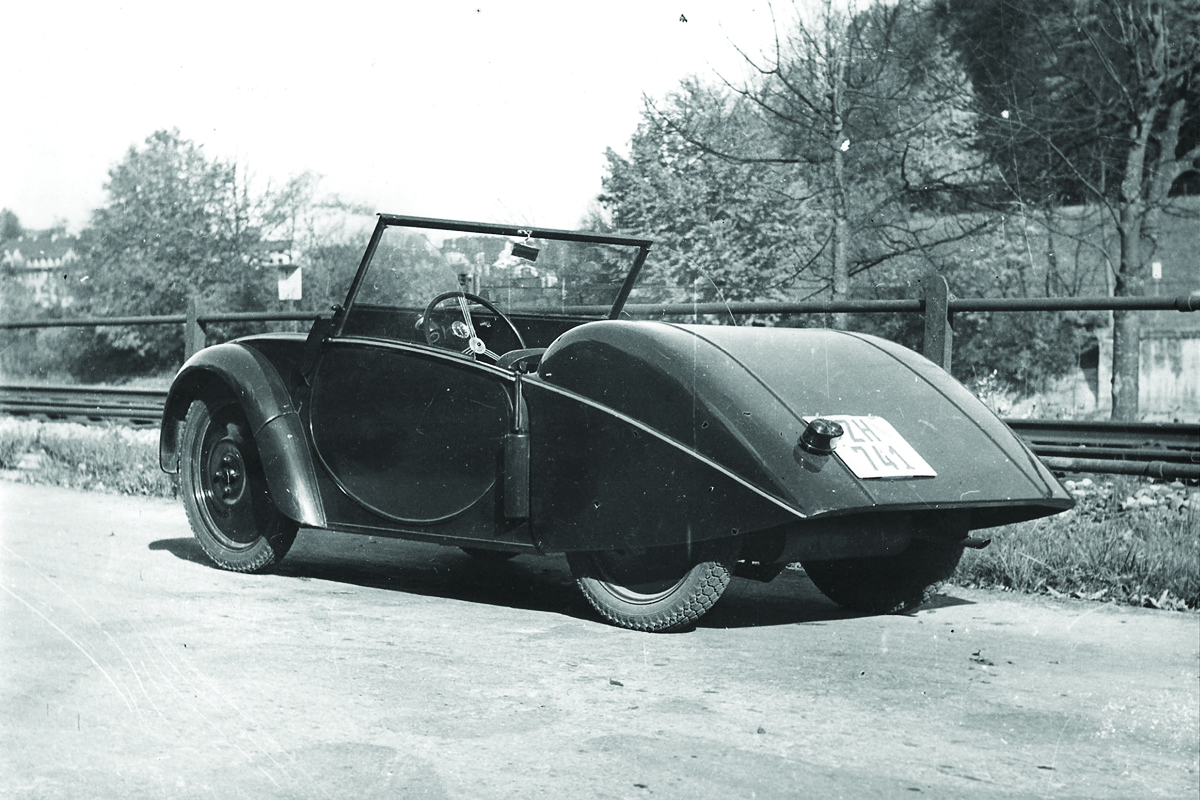

By February 1933, Josef had finished his first model to go into full production known as the Standard Superior. This is the car often confused for the first KDF VW Beetle, which wasn’t really a running prototype until 1935. It’s clear why though as it shares pretty much every major feature with the early Beetle.

The Standard Superior was unveiled at the IAMA (Internationale Auto und Motorradausstellung) in Berlin. The show was of great importance to the time. The grand opening was to be carried out by Adolf Hitler, it was to be his first major public function as Chancellor of Germany. During the duration of the show, Josef stood just meters away as Hitler expressed interest in the Standard Superiors design and especially its low selling price of only 1,590 Reichsmark.

Hitler started making sketches of the car but never acknowlededJosef due to his anti-Semitic beliefs and the black mark left on his name due to his opposed writings in Motor-Kritik. These drawings were supposedly passed on to Ferdinand Porsche, who Hitler had by this time in his pocket, working closely on their new project the KDF (’Strength Through Joy’) movement.

The first Standard Superior model had a short production run of around 250 units but was well known to be an innovative design causing quite a stir within the motoring industry. During 1935, whilst Ferdinand’s first KDF wages prototypes were being successfully tested, Hitler ordered Josef to be arrested by the Gestapo and all current work and records to be destroyed. In fear for his life, he had been given no choice but to flee to Switzerland – where he settled for the next 6 years still chasing his obsession and started trying to develop a people’s car for the Swiss. In 1951 after a job offer he couldn’t refuse, he moved to Australia and went to work for Holden (the General Motors subsidiary). Not much is known about this period of his life, until in 1965, when he decided to tell his story to the Australian Motor Sports and Automobiles magazine he self-titled “How I Invented the Volkswagen”.

In 1967, at the age of 69, Ganz sadly passed away.

The more I think about “How I Invented the Volkswagen” It’s a very bold self-title… How much truth there is in this statement has to come down to a matter of personal opinion. At the end of the day Josef is just one of several engineers considered to have a rightful claim to being the Beetle’s creator. Other research states that key ideas came from Bela Barenyi, an engineer at Daimler Benz, who invented the crumple zone and other safety features. Hans Ledwinka of the Czech Automaker Tatra, who we discussed in Issue 22. Both Hitler and Josef had seen the new Tatra 77 previously. Plus many more similar cars, the rear-engined Mercedes 140, 150 and 170H models, the oddball Bungartz Butz. Porsche himself designed two VW-like model in 1931-32 – one for Zundapp and another for NSU.

So, without Ganz would the Volkswagen have ever existed?

I personally think it would but maybe not quite as we know it. In my opinion, the Beetle was a melting pot of innovative ideas of the time. Some original, some stolen and some genius.

One thing I am sure of is that ’Ideas Thief’ is another insult we can throw at the murderous dictator.